Critic’s Lens: Performing Fluxus

Noël Carroll’s Living in an Artworld collects essays that showcase his body of work as an art critic in New York in the 1970s and 1980s.

Comprising, for the first time in one volume, an anthology of Carroll’s influential reviews of dance, performance art, theater, and fine art events and exhibitions in New York, along with philosophical essays on these topics ranging from 1978–2007 (with the majority originally published between 1978 and 1984), this text provides an invaluable insight into the avant-garde New York arts scene of the late seventies and early eighties, seen through Carroll’s philosophically astute lens. Following a foreword by Arthur Danto, in which Carroll’s critical and philosophical writings are presented as a valuable “downtown” counterpart to the “uptown” aesthetics of this time that focused more exclusively on more traditional arts of painting and sculpture, this volume is divided into sections featuring reviews and essays on “Dance,” “Performance and Theater,” “Fine Art,” and later reflections on the conceptual and global implications of the characterization of the art movements in this period as postmodern in the final “Coda” section.

Dancer Yvonne Rainer

Carroll situates the focus of this anthology on arts that share a commitment to exploring the idea of perceptual indiscernibility between art and life that was beginning to taking center stage in avant-garde and mainstream art circles during this time, an idea that features prominently in Danto’s seminal philosophical writings on art. Arguing that the blurring of boundaries between ordinary objects or events and art works and between traditional and non-traditional art media in the work of artists like Cage, Rauschenberg, and Warhol motivated a fruitful conceptual period focused on exploring these same boundaries in other forms, Carroll emphasizes a similar integration of ordinary movements into the various performing arts featured in many of the reviews in this volume.

Dancer Merce Cunningham

The reviews themselves (some co-authored with dance critic and historian Sally Banes) are concentrated in the “Dance” and “Performance and Theater” sections of this text.

Encompassing many art criticism pieces originally featured in a range of publications including Artforum, Dance and Dancers, Dance Magazine, Soho Weekly News, and the Village Voice, they cover a wide array of artists and performances embedded both centrally and fleetingly in the downtown New York performing arts scene of this time period — with the notable inclusions of artists like Merce Cunningham, Yvonne Rainer, and Ishmael Houston-Jones — addressing a range of topics including minimalist dance, reactions to formalism and expression in dance, the attention to everyday movement in dance and performance, Black avant-garde performance art, and popular culture in performance, serving as valuable resources for dance and performance scholarship and the philosophy of dance and performance. These are intertwined with essays on the conceptual analysis of the dance, theater, and performance arts featured in New York in this time period, among which is a key essay on the art of performance, all particularly timely in the context of both revived attention to the artists of this period in the contemporary New York performance arena and growing academic attention to the philosophy of dance and performance studies.

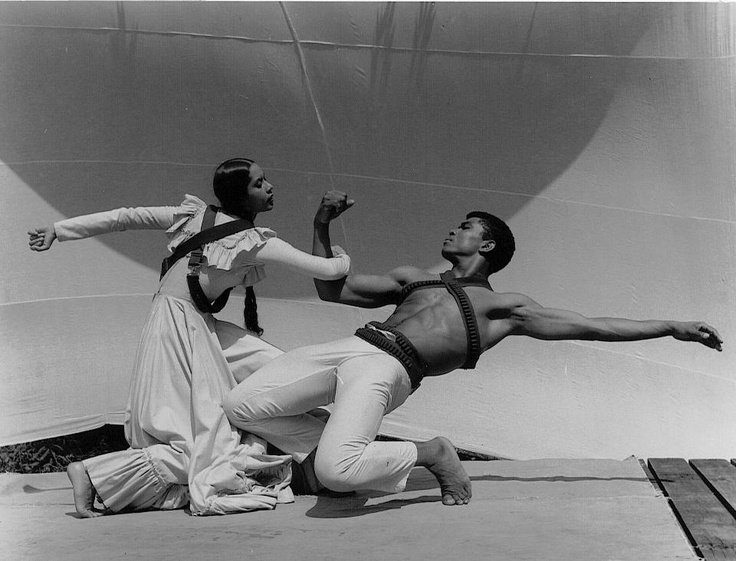

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

The “Fine Arts” section in contrast compiles primarily philosophical essays analyzing concurrent fine arts works and artists in the seventies and eighties, especially in relation to the concept of the postmodern, broader conceptual attention to which is the focus of the final “Coda” section. The volume ends with a notable (though much more general in focus) essay on globalization.

Though the reviews in particular seem at first more narrowly useful to readers with a specific background and interest in performance arts of this period (with the exception of music, which is not strongly featured), rather than to those interested in their conceptual categorization, Carroll’s characteristic clarity and philosophical framing of each section render them accessible to readers less versed in these areas of scholarship, such as upper-level undergraduates pursuing the philosophy of the arts. Beyond this, however, I see this text also serving as a thought-provoking supplement to scholars and teachers more interested in broader philosophical issues on two counts.

Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (1964)

First, the essays and reviews combine example cases most commonly taken as paradigmatic in Analytic philosophy of art addressing distinctions between art and non-art — such as Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917), Cage’s “4’33”” (1952), and Warhol’s “Brillo Box” (1964) — with a rich array of philosophically relevant examples in performance arts. These performance art examples situate these more commonly cited cases within a cultural and historical narrative on the artistic legacy and impact of these works in the New York arts arena of the 1970s and 1980s while also providing valuable philosophical context to examples that are often taken in isolation in philosophical analysis of the arts. This provides a more comprehensive and contextualized range of examples for theorists and teachers interested in situating, extending, and testing the scope and boundaries of philosophical claims about indiscernibility with respect to performance arts and also across multiple arts, as well as for those interested in the conceptual interrelations between art forms perhaps more commonly treated separately in philosophical analysis.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917)

Second, though the pairing of art criticism reviews and philosophical essays in the anthology might resist its categorization as either a strictly philosophical or performance studies text, it presents an engaging and critically interesting meta-narrative that plays with the extent to and manner in which philosophy and art criticism do, can, or ought to engage and intersect with each other, Yvonne Rainer’s recent revivals, following the death of Merce Cunningham in 2009, of seminal performances like the 1966 Trio A (2010), with the Judson Dance Theater reflect a resurgence in New York dance of interest in artists and movements of the sixties and seventies, intersecting with the focus of many of Carroll’s reviews in this text, raising stimulating questions about the relations between these varied and often hybrid approaches toward the analysis of the arts and their comparative descriptive and critical value.